DevOps is hard.

Not necessarily the technology, nor even the concepts. The hard part is that you're being asked to set up a series of things without knowing all the answers. Things like:

- what's the capability of the engineers?

- how are we going to work and release software?

- what infrastructure do we have?

I'm regularly asked "what is your go-to workflow?" so I thought I'd actually do a fully-worked example and upload it to GitLab for you to follow along. This is a simple NodeJS app that outputs the number of database records, the version of the software and the value of a given secret (terrible in a live environment, but fine for demo purposes).

Important: this won't be everything. With all software, there are nuances. But this is my usual starting point.

Guiding Principles

Before we go into the details, I've tried to follow some principles. These are principles that I find keep the unknowables to a minimum and reduce what you actually have to support.

Follow a pattern

Yes, design patterns exist in DevOps. I'm a fan of the GitOps pattern as it allows rapid deployment without having to store credentials everywhere.

Use managed services where they exist

As a software house, your specialism is the software that you make. You may have the job title "Database Specialist" or "Kubernetes Guru", but you are still only one person. The cloud providers have many people working on each service they provide. If there are managed services available, the cost of using those managed services are worth not having to worry about replication, backups or upgrades. Specifically, unless you absolutely cannot avoid it, use managed Kubernetes and databases. And if you're using a database that doesn't have a managed service, look for a Helm chart maintained by the original authors, or experts like Bitnami.

Don't write your own toolchain

It's so easy to make mistakes. Especially in a pipeline where it may be hard to simulate all manner of loads or configurations. Use something that's reliable. In my pipeline, I use GitLab and Terraform Cloud because they're robust and well-tested, and they're flexible enough to allow me to use them in the way that they're intended.

Don't get vendor-locked

All the main cloud providers provide their own SDK. And I'm well aware that, as a business, there may be a very good reason why you're using AWS/Azure/GCP/DigitalOcean today. But what if that reason goes away? They might suddenly raise their prices, or drop support for something that you view as crucial. I would always advocate provisioning infrastructure in Terraform or Pulumi because they support all cloud providers - personally, I find these dedicated provisioning tools easier to learn and use and far more flexible than using the cloud provider's SDK.

NB I really like the concept of Pulumi, but it's missing a few really useful features. The one I miss the most is the option to create a plan, save it and then apply the changes in that plan. This is supported out of the box in Terraform but not yet supported in Pulumi.

Requirements

Let's highlight some business requirements for our application. Of course, these will be different in each case, but they should be fairly middle-of-the-road for many applications.

- Use a private Docker registry

- Standard three-stage (dev, staging, prod) environment

- The ability to set each environment to any version of the application

- Kubernetes to handle the orchestration

- A managed MySQL instance

- LetsEncrypt SSL certificates automatically generated for all endpoints - configurable to dev certs if we wish

- Helm charts to manage the application

- Automatic database migrations

- Sealed Secrets to keep credentials safe

In this example, the infrastructure is managed using Terraform Cloud. This was purely for convenience of this example - in production workflows I've used both GitLab (and others) to provision the infrastructure and Terraform Cloud.

The Workflow

1. Building the Infrastructure

This is handled by Terraform Cloud. Changes are triggered either when a change has

been committed to the repo or when an authorised user triggers the change. The building

of the infrastructure take a plan and apply approach - Terraform works out what

will happen, you approve it and it then makes the changes.

Once this has finished, a webhook to GitLab is triggered to move onto the next stage.

NB. Terraform Cloud separates each environment into a "workspace". If you want to trigger any additional environments (eg, staging and prod), do so now.

2. Provision the Environments

Once GitLab receives the webhook, it runs various configuration jobs. These are

named in the .gitlab-ci.yml file and are mostly explanations in themselves, but

to list them:

- add_docker_registry_secret: Adds the GitLab Docker registry credentials to be able to get the container images

- add_mysql_secret: adds the managed MySQL host, username and password to the K8S cluster

- install_cert_manager: Installs Cert Manager to the cluster, to generate LetsEncrypt SSL certs

- install_gitops: the GitOps workflow requires various workers in the cluster to be able to pull new images to container, based upon configurable rules.

- install_nginx_ingress: Creates a load balanced ingress controller on the cluster, using Nginx

- install_sealed_secrets: Installs Sealed Secrets

Now we're at this position, we have a fully provisioned cluster but nothing deployed to it. Because we've got GitOps configured, we now need to consider what we're releasing.

GitOps 101

GitOps is brilliant.

This solves a few of the main problems with an automated workflow neatly. One of

the biggest legacy issues with any deployment workflow is the question of passwords

and keys. Originally, in the days of Dev and Ops, you may have had SSH username/password

specifically for the Ops team - they'd have gone onto the server, downloaded the

new artifact and set it to live. Later on with Kubernetes, you could set the CI/CD

pipeline to run helm up but still you had to store the kubeconfig.yml file

somewhere in your infrastructure. Ultimately, all of these have the possibility

of a bad actor getting hold of these credentials and wreaking havoc.

GitOps is different. All of those methods were "push" based - ie, someone-or-something decided to push a change to a server. GitOps is "pull" based. That means you have a release manifest detailing what you want in your release and it then pulls it down to the cluster when it finds a change.

This probably seems quite daunting at first, but this is the way most package managers

work - it's certainly how npm works. When you want to install a dependency, you

will typically allow for a range of versions - you might have express@^4.0.0 in

your package.json, which mean you want anything that matches v4.x.x.

Now take a look at /releases/dev/app.yml:

---

apiVersion: helm.fluxcd.io/v1

kind: HelmRelease

metadata:

name: app

namespace: app-dev

annotations:

fluxcd.io/automated: "true"

filter.fluxcd.io/chart-image: semver:^1.0

spec:

releaseName: app

chart:

git: git@gitlab.com:MrSimonEmms/example-deployment.git

path: charts/app

rollback:

enable: true

values:

image:

repository: registry.gitlab.com/mrsimonemms/example-deployment/app

tag: 1.2.0

ingress:

host: example-deployment-dev.simonemms.com

You will notice filter.fluxcd.io/chart-image: semver:^1.0. That simply means

that we will automatically pull down any new release in the v1.x.x range. Now

compare it to staging

semver:~1.1- and prodsemver:~1.0. This lock the automatic releases down to those ranges.

And when we want to move prod to the v1.1.x range? Well, that's as easy as creating a pull request to update the code with that single line changed.

To provde it all works, here are some screenshots of my app in their three different environments.

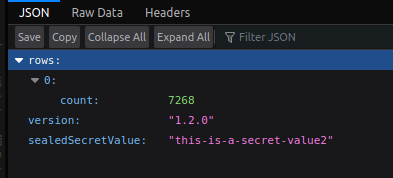

Dev

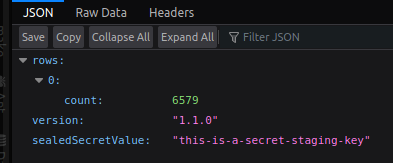

Staging

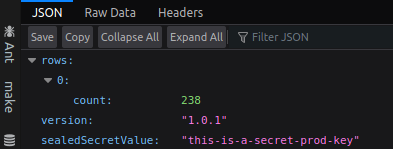

Prod

All the same app, all different versions, all with the secret visible.

Versioning Your Releases

One thing all this is predicated on it having all your releases versioned. For me,

that is a new version created every time a new commit hits the master branch.

You may notice that I use a "strange" commit message format - feat(<scope>): message.

This is called Semantic Release and is very

useful for keeping track of your releases.

And once you've got unique versions for everything, you can easily rollback.

There you have it, this is how I recommend setting up a DevOps workflow. Of course, this is very much just an overview but this is tried-and-tested and something I've used for a long time and with a good number of clients.

This makes releases rapid - with this workflow, there's no reason you cannot do multiple production releases per day. For the developers in your team, this just becomes a question of getting a PR approved and passing their CI/CD tests. And for your DevOps team, this is completely self-managing allowing them to focus their time on more important things like performance, scalability, reliability and security.

Credits

Photo by Mike Benna